Today, we’ll talk about the second most important question Jerome Powell and his Federal Reserve will be deciding in its September.

Some dramatically claim when the Federal Reserve governors meet in September, they will be making making the decision on who wins the Presidential elections come November. Indeed, Trump and Vance have been questioning the Fed's authority to independently determine interest rates which drive much of the US and, perhaps, the world economy.

We will leave the politics aside for a moment, and talk about the second most important decision Federal Reserve will make this September: should it cut the interest rates by 25 or 50 basis points - or in an unlikely event, not at all.

Today’s Report is brought to you by Public Radio Listener. It’s a new way of finding the most relevant broadcast to go along with what you are reading. Try this new service, it will change how you “read” news.

Strategic Insights Report is powered by our readers. We provide exclusive and comprehensive coverage of crucial yet often overlooked business and political developments, including our detailed economic analyses based on 100s of expert interviews. Subscribe today to join a community of forward-thinking professionals who depend on our indispensable business insights.

When the Federal Reserve governors meet this September, they will be grappling with an economic landscape that presents a complex mix of data points and trends. Until July, the U.S. economy had experienced 42 consecutive months of job growth, with unemployment near historic lows. This exceptional recovery, of course hides some undercurrents of weakness: wage growth has moderated, with average hourly earnings increasing by 4.4% year-over-year in July, down from the peak of 5.9% in March 2022. Jobless rate has started picking up, with more disaffected workers reentering the job market, rising to 4.3% in July compared to 3.9% in May. Yet, U.S. GDP grew at an annualized rate of 2.4% in the second quarter of 2023, contrasting with the World Bank’s projection that global growth will slow to 2.1% for the year—the weakest in three decades outside of major crises. But nobody thought we’d go from 10% inflation to 2’s without a recession.

This economic “good news” complicates the Federal Reserve’s decision-making process. Labor productivity surged at a 3.7% annualized rate in the second quarter of 2023, marking the fastest pace since 2020, while the U.S. dollar has strengthened by 6.5% against a basket of major currencies over the past year. At the same time, the federal funds rate is currently at its highest level since 2001, and personal consumption expenditures inflation, as measured by the Fed’s preferred gauge, is running at 2.5%, down significantly from its peak of 7% in June 2022.

"This situation is highly unusual," confides a senior Fed economist, speaking on condition of anonymity. "Typically, we cut rates when the economy falters. But now, with 11.5 million job openings and wage growth at 4.4%, we're debating a move that could further accelerate an already heated economy."

Cue the Fed’s “fairness doctrine.” This new approach, championed by Jerome Powell’s Fed is introducing a new way of thinking about economy - not purely in terms of an economic balance between inflation and jobs, but fairness where a more political Fed pushes aims to create an opportunity for fair economic growth. If the term sounds more political than economic it is. Over the years as Fed has become more powerful, it has taken on more responsibilities traditionally held by political and elected bodies. Many at Fed and those with knowledge suggest that Fairness is at the core of its likely decision to start bringing rates down as soon as September, despite an upcoming election and and economy that doesn’t seem to need the rate cuts.

This unconventional approach, if pursued, would mark a significant departure from the Fed's actions over the past 18 months, during which it raised rates 11 times before pausing, moving from near-zero to the highest level in 22 years.

Echoes of the Past: Comparing Today's Economy to the 1970s

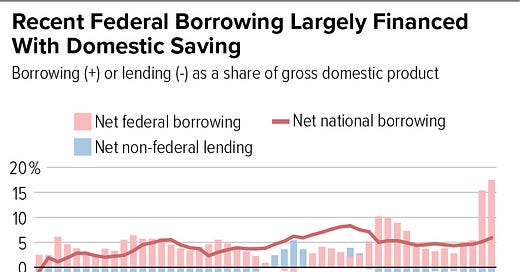

As we covered in our earlier Report, many question both the current strength and potential future weakness in the US economy. These economists believe the economy is built on a house of cards and Fed is deluding itself in thinking it can control an economy where borrowings now exceed its economic output.

Others remind us how asset bubbles are formed. “A rate cut in this climate could propel the S&P 500, already up 17% this year, to new heights, potentially inflating asset bubbles. It might spur a wave of corporate borrowing, adding to the $11.3 trillion of outstanding corporate debt. On the global stage, where the dollar remains the dominant reserve currency – accounting for 58% of global foreign exchange reserves – any shift in U.S. interest rates sends shockwaves through international markets,” notes a senior analyst at a Wall Street bank. “It would be foolhardy to believe Fed can cut interest rates and markets wouldn’t react.”

Perhaps most concerning is the question of future resilience. By deploying rate cuts now, in a time of relative prosperity, the Fed risks depleting its arsenal to combat future economic downturns.

Practitioners dismiss these worries as academic, a word representing a lack of application. "Their [Fed] goal right now is to keep the soft landing going," observed Julia Coronado, founder of MacroPolicy Perspectives in a New York Times article. "So why risk tightening policy? Now the challenge is balancing risks." This sentiment captures the sentiment pervasive within the practitioners.

In a sharp rebuke to academics projecting a return to 1970s-style high inflation, practitioners argue that the economic landscape today is fundamentally different. A senior economist at the Boston Federal Reserve, who requested anonymity, remarked, "The economic landscape we navigate today shares little with the stagflation-triggering era of the 1970s. We're informed by decades of data and a fundamentally evolved economic structure that were absent in past crises. Unlike the 70’s when an oil embargo crippled the US economy, we now net exporters of energy in the US. At Fed, too, we are no longer working on a hunch and trying to come up with theories. Our decisions are data driven, and data tells us we are making the right and fair call." Data, of course. But - fairness again.

However, this evolving debate also highlights the risks associated with any policy decision, particularly one as consequential as a rate cut. Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, warned in a January speech, "Premature rate cuts could unleash a surge in demand that could initiate upward pressure on prices." These cuts that were previously suggested as early as March haven’t come so far as economy continues to surprise with its strength. Economy hasn’t done poorly in past few months, either. Rightly or wrongly, then, many question Fed impartiality in cutting rates so close to elections when economy seems to be doing fine on most measures.

In writing this Report, we had to explore why the Fed is contemplating such an unorthodox step and what it could mean for America's economic and political trajectory. Is Fed political if it makes the decision or apolitical by making a political decision in face of the heat it knows it would face? In an era where the Phillips Curve – the inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation – seems to have broken down, the Fed's next move may well redefine the boundaries of monetary policy for a generation.

Time to Act

The contrast between these strong U.S. indicators and slower global growth is stark. The U.S. economy expanded at an annualized rate of 4.9% from July to September 2023, the strongest pace since 2021, defying earlier predictions of a recession due to the Fed’s aggressive interest rate hikes.

“While this growth has since been moderated, GDP growth rate has continued to surprise on the upside, puzzling many economists. The strength of economy has tested many theories. Of course, the current strength in economy shares that with past bubbles,” warns an economist who recently left Federal Reserve.

These numbers underscore the complexity of the economic puzzle that the Federal Reserve faces as it approaches its September meeting. “Traditional relationships between economic indicators appear to be shifting, challenging conventional models and complicating the Fed’s decision-making process,” the economist continues. “This is what’s so worrying about the current economic environment. While there are no obvious signs, these breakages suggest a larger underlying problem. In economy: everything is fine, till it isn’t.”

A senior economist at the Boston Federal Reserve, speaking on condition of anonymity dismisses these concerns. "Many were fearing Fed actions would trigger a recession. But our close cooperation with Treasury and timely intervention seems to have brought us close to a balanced economy.”

She explained, “The economic challenges we face today are vastly different from the stagflation era of the 1970s. Many academically minded economists learnt their economic lessons in the 70s, but I am afraid many of them have learnt the wrong lessons and started to question American economy a little. The bogies of welfare state, greed, speculation - these are just that, bogies. Given its diversity, US economy has a self healing quality and only needs small nudges from time to time. So long as these ‘nudges’ are timely, they don’t have to be drastic and can be reversed without resulting in catastrophic inflation or other long-term challenges."

This sentiment is widely shared within the Federal Reserve, where many view the current situation as the result of a deliberate and measured effort to steer the economy away from disaster. A former Federal Reserve economist, now leading a quantitative hedge fund, sees the potential rate cut in September as a defining moment: "This isn’t just another policy shift; it's Chair Jerome Powell’s chance to secure his legacy, much like former Fed Chairs Paul Volcker and Alan Greenspan. Successfully navigating this transition could place him among the ranks of the greatest Fed Chairs in history.”

However, caution remains a central theme for others within the institution. Raphael Bostic, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, recently warned, "Premature rate cuts could unleash a surge in demand that could initiate upward pressure on prices." His caution reflects a deep-seated concern that even in a vastly different economic environment, the fundamental risks of inflation remain.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Strategic Insights Report to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.